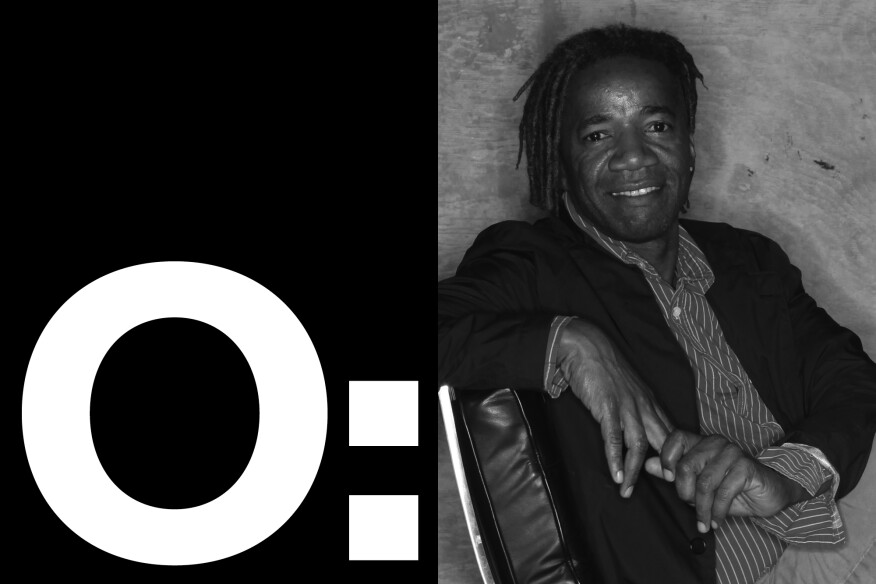

Walter Hood: Bespoke Landscapes, for the Past and Future

Walter Hood: Bespoke Landscapes, for the Past and Future

The Oakland, Calif.-based landscape architect shares how successful urban landscapes are unique reminders of a community's heritage.

By Walter Hood

As chronic diseases soar and physical activity shrinks among America’s residents, it’s clear that a community’s physical condition has implications for residents’ health and well-being. Research shows that life expectancies and quality of life are linked to social and built environments. We don’t need studies to recognize that fresh air, green space, and safe streets are nowhere close to evenly distributed.

In these times, thinking about urban landscape design as a smattering of cookie-cutter playgrounds and community gardens isn’t enough. Frankly, it never has been. We must approach landscape architecture in terms of functionality, an area’s history, and residents’ specific wants and needs, be it more green space in dense urban settings or community gardens and game areas to promote collaboration and interaction. All of these missions must be executed with an unerring focus on sustainability, ecology, and equity.

That has been the premise behind Bronzeville Lakefront, a 100-acre development on Chicago’s South Side that includes the former Michael Reese Hospital site. It offers an opportunity to implement forward-thinking urban landscape design principles without erasing the past.

Reimagining Urban Landscapes

First, there’s the principle of place. A landscape isn’t simply a physical environment; it’s a reminder of heritage. Streets, sidewalks, trees, and tracts of land are all imbued with history that spans vast periods of time. There’s heritage there.

Bronzeville was formerly a bustling Black metropolis. The Great Migration saw more than 6 million Black people leave the American South for the urban North in the first half of the 20th century, and the Bronzeville neighborhood became a thriving center for Black arts, culture, and entrepreneurship. Even as the early 20th century witnessed many injustices and sorrows for Black Americans, there was also an abundance of Black joy in Bronzeville as thousands of people of color experienced it as a thriving environment where everyone felt welcome to congregate in the streets.

"It’s crucial that Bronzeville Lakefront’s landscape incorporates built spaces that feel safe and accessible for community members. A sense of alienation can occur through built landscapes, which often happens when developers or landscape architects erase everything."

In the first half of the 20th century, a bustling stretch of Bronzeville’s State Street known as “The Stroll” was home to a cornucopia of jazz and blues nightclubs frequented by the likes of Louis Armstrong, Nat King Cole, and Jelly Roll Morton, as well as ballrooms, theaters, and other businesses.

Bronzeville Lakefront must pay homage to that era, while also crafting the South Side of the future. With innovative landscape design, this regenerated community can create a thriving environment with robust outdoor spaces such as fitness courts, outdoor dining areas, eco-themed gardens, and playgrounds. A new stretch of Cottage Grove, another major artery in Bronzeville, is being added in Bronzeville Lakefront to facilitate better transit access, and it will be brought back to life with features like bespoke benches and hatches positioned to resemble a jazz score. New pockets for outdoor dining and seating areas in this development, and along Bronzeville’s major streets, can, and hopefully will, become characteristic of the entire neighborhood and create space for residents to mingle, relax, enjoy the land, and be joyful.

Innovative urban landscapes must also incorporate an area’s ecology. Ecology of place is rarely talked about in communities of color. Bronzeville Lakefront is bound in the east by Lake Michigan, which creates a series of green “ribbons,” lush stretches that run parallel to the waterfront, enabling healthy living while referencing the woodland, wetland, and dune habitats.

Finally, there’s the idea of belonging. It’s crucial that Bronzeville Lakefront’s landscape incorporates built spaces that feel safe and accessible for community members. A sense of alienation can occur through built landscapes, which often happens when developers or landscape architects erase everything.

Our design studio often uses the term palimpsest, something that has diverse layers, apparent beneath the surface like coats of paint revealed as they peel. The idea is to identify elements of a landscape from the past that resonate with people today, and to leave those elements undisturbed. In a previous project, we left the public sidewalk, where people had written their names and stains remained from long ago. In other words, there’s life there. In Bronzeville Lakefront, we’ll keep elements of the original landscape intact so that residents continue to see their legacies alive.

Redefining Success in Urban Landscapes

I believe a successful landscape design is a matter of sustainability—from an environmental and social standpoint. The best design remains intact for generations and stays accessible, welcoming, and recognizable to longtime residents.

One example is Lafayette Square Park in Oakland, Calif., a project Hood Design Studio completed in 1999. The process included building in traces of the park’s origins and providing for a diverse array of visitors and varying needs, from game and performance spaces to picnic areas and playgrounds. More than 20 years later, the park still stands, and Black residents are still visiting; they didn’t get pushed out. Another example is Splash Pad Park in Oakland, a project under a freeway that few thought could sustain itself. It is now approaching its 18th year and is home to Oakland’s largest weekly farmers market.

Dissimilarity is another marker of success. If a finished project looks atypical, like it wouldn’t exist anywhere else, that typically means landscape architects have done their job. With any project, the endgame should not be sameness. Each landscape has a different history; landscape design should be bespoke, reflecting the particularities and genealogy of place.

When it comes to Bronzeville Lakefront, regenerating a long-vacant tract of land to meet expansive and exacting objectives for a new era is a significant undertaking, a vast enterprise that involves developers and community stakeholders, commercial and residential buildings, lofty visions and rooted histories, healthy living targets and high stakes. Landscape architecture is just a fraction of Bronzeville’s larger transformation, but it’s also a pathway to tap into a cultural tapestry that draws on Bronzeville’s rich history while telling new stories.

The views and conclusions from this author are not necessarily those of ARCHITECT magazine or of The American Institute of Architects.